By Hembree Brandon

Farm Press Editorial Staff

Noxubee County, which borders the Alabama line in the rolling prairie land of north central Mississippi, is one of the state’s most agriculturally diverse counties.

There’s the usual row crop mix — corn, cotton, soybeans, wheat — to which is added cattle, catfish, poultry, dairy, tree farming, hunting/fishing operations … and sheep.

Sheep? In Mississippi?

Yes, thousands of ’em. But they’re not the downy animals that grow your winter sweaters; these are hair sheep, grown for meat to serve the appetites of an increasingly large Mideast and African population that favors lamb.

And while Steve Koehn laughs and says, “Anybody’s got to be a little nuts raising sheep in this part of the country,” he’s been doing it for five years now and admits to being “reasonably successful” at it.

There are several sheep herds in the county, and while he declines to give exact numbers for his own herds, which are spread out on hundreds of acres over three locations, he says they’re “in the thousands” and that he and his partner, Myron Unruh, “have the bulk of those in the county.

“Honestly,” he says, “I’m not sure sheep are a particularly good enterprise here, given the summer heat and humidity and the parasite and disease problems you have to contend with.

“This isn’t like turning cows on pastures and checking on them every few days. This is an everyday business; it’s a lot of work, and there’s hardly a day goes by I don’t encounter something new. When we’re lambing, it’s 24/7 for about three weeks.

“I grew up with cattle, but sheep are more difficult — more health issues, and they require daily attention.

Demanding business

“We’ve been able to make it work because we’re willing to put in the time and give the animals the attention that’s necessary, but it’s a very demanding business that not a lot of people want to do. And like anything involving livestock, we’re at the mercy of market prices. This past winter’s prices were excellent — but that’s not always the case.”

Koehn, who sports a cap with the message “Eat lamb,” is a native of Kansas, who had previous experience with cattle and sheep out west.

“We were living in Arizona and a cousin from Mississippi, who would come out for the winter, talked us into moving here. We’ve been here 15 or 16 years and really like it. We started in the sheep business because of a lack of acres to run a lot of cows. We could run more sheep per acre.

“There’s no realistic formula for animals per acre — it all depends on weather, grass, etc. We figure we can run two to three head of ewes to one cow/calf unit.”

Koehn also has a business seining catfish (Noxubee County is the second largest catfish-producing area in Mississippi outside the Delta).

“When I moved here, I initially worked for area catfish companies, and then later started my own business servicing producers. That’s pretty much a year-round thing.”

His sons, Jeremy and Douglas, help some with the operations, and he gets some additional help, as needed, at lambing time, rounding up the sheep, and other chores.

“We’ve just finished lambing,” Koehn says. “The lamb crop was about 150 percent, which is quite good; there were a lot of twin and triple births.

“Winter is the prime time to sell lambs, so we try and schedule our breeding program so we’ll be able to sell lambs during that period.”

But raising summer lambs in Mississippi is a challenge, he says.

“The problem is that on grass it takes five to six months to get a lamb to the desirable weight of 70 pounds to 80 pounds. So, we end up lambing in April, which then means these young animals are going to have to go through the high heat and humidity of our summers, when the grass goes to pot and the ewes aren’t producing milk as well.

“It’s rougher on them here than out in the western states, where herds can be moved to higher, cooler elevations for the summer.

“You can lamb in March, as we did this year, when you have the flush of spring grass, but then you’ve got lambs coming off in August/September, when the market’s poor and a lot of other producers have animals to sell at the same time.

“Ideally, we’d be lambing May 15-June 15, so we’d have lambs for market during the prime winter market period.”

He says there is a packing house in Memphis that handles huge numbers of both sheep and goats.

Hanging weight

“We rarely run our animals through sale barns; we have a relationship with a buyer, and work mostly through him. We’re paid on hanging weight (after the animal is slaughtered and on the rails) rather than live weight.”

The hair sheep are mostly crossbreeds, Dorper and Katahdin, with some straight Katahdin — and, unlike wool sheep, they shed their coats in the spring (fences and tree trunks are matted with great hunks of hair the animals have rubbed off).

Pastures are mostly fescue, clover, and native grasses. During winter, Koehn says, “We’ll feed some hay and straight whole corn. The last couple of winters, we had 500 lambs on full feed all winter long.

“Sheep will eat almost any grass, and some weeds, such as buttercup which blankets fields in spring. They love johnsongrass — if they got into somebody’s corn field, they’d eat the johnsongrass first.

“You can take not very good ground and do OK with sheep. This area has a lot of limestone soils that aren’t good for much of anything else, but they will grow grass. The sheep are particularly good for grazing land around catfish ponds.

“We save back a lot of ewes for breeding and buy some from Bill Mason, a Tennessee veterinarian, who has done a lot of work breeding sheep for parasite resistance. Parasites are a major problem in this part of the world. Mississippi heat, humidity, and a lot of rainfall — that’s a perfect combination for parasites. We had a bad round of liver flukes this winter and lost a lot of animals. That was a real bummer.

“We try not to deworm excessively, maybe three times a year. We vaccinate the ewes for multiple diseases — blackleg, rednose, etc. This is very important to herd health. We probably lose 3 percent to 5 percent of our herd to diseases, parasites, and predators.”

Predators are mostly coyotes and domestic dog packs. “Coyotes will usually go for the lambs,” Koehn says, “and those losses are relatively minor, but packs of domestic dogs can be absolutely devastating. We recently had a really bad dog kill and lost 13 lambs.”

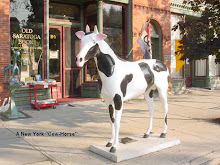

He keeps guard dogs with the herds, but in one field there is what he laughingly calls his “guard horse.”

“It’s the craziest thing — this mare has bonded with the sheep. She’s better than any guard dog; she’s ferocious if she thinks anything is going to bother the sheep. You’d better not mess with her.”

The guard dogs are Anatolian shepherds and Anatolian/Pyrenees crosses.

“They’re really antisocial,” Koehn laughs, as he circles his pickup around a herd, trying to spot the dogs. “They’ll usually come up when I come out to feed them, but they live for the sheep.”

The Anatolian/Pyrenees cross, so shaggy he blends in with the herd, is “a really weird dog,” he says. “He’ll be right there with the sheep until he croaks. If his herd got out and roamed all the way to Louisiana, he’d be right there with them, protecting them.”

Border collies

For herding the sheep, Koehn relies on border collies. Tucker, the border collie riding in the pickup with him, is two and a half years old, and “has got a pedigree that’s out of this world — he’s a really fine dog.

“These dogs can do what men can’t. They demand respect from the sheep, and they get it. I can send one out to round up a herd, and he’ll bring ’em right to the corral.

“A sheep man without trained dogs would just be lost. These dogs will absolutely go until they drop. A good trained dog can cost several thousand dollars, and it’s a real blow when we lose one.”

But, he notes, they can be insured, just like people.

Bryce and Donald Allsup, who live in the area, “are really great sheep dog trainers,” Koehn says.

For breeding, Koehn says, they have one ram for every 30 to 35 ewes.

“We try to buy good registered rams. We use more Dorper rams and Dorper ewes because of the meat quality and to put bulk on the lambs. Meat from hair sheep is less strong than from wool sheep — it’s a really mild meat.”

Koehn cooperates with the Mississippi State University School of Veterinary Medicine in hosting students who want go get firsthand experience with sheep, and says Dr. Sherrill Fleming, associate professor of veterinary medicine, “is a great help when we have problems or need advice; it’s always a pleasure working with her and her students.”

e-mail: hbrandon@farmpress.com

http://license.icopyright.net/user/viewContent.act?clipid=297865885&mode=cnc&tag=3.5466%3Ficx_id%3Ddeltafarmpress.com%2Fnews_archive%2Fmeat-sheep-0527%2Findex.html

No comments:

Post a Comment